Playing games like Skyrim, Grand Theft Auto, Assassin's Creed: Black Flag, The Witcher 3, Mad Max, Metal Gear Solid V, and other open-world games has made me increasingly weary of open-world gaming. Narrative-based, open world games like these suffer from a problem that I have started calling "open world limbo" (or "open world purgatory"). This is a sort of paradoxical offshoot of the concept of ludonarrative dissonance. The game's open world "sandbox" design seems to directly conflict with the narrative that the game is trying to tell. It specifically refers to the conflict between the story and the game's open world, rather than a conflict between the game's story and any particular game system(s). Generally, this manifests as the game designers setting the stakes so high that the player should feel pressured to progress the narrative, but the game's open world design never follows through with any real consequences for not progressing.

More and more big-budget games are going open world. is this a good thing?

This leads to problems in which the player can spend hours, weeks, or months doing tangential, or completely unrelated, tasks and pushing the game's story objectives down to the bottom of their priority list. For people who just like to play the game, this may not be much of a problem. They get a massive sandbox in which to do anything they want. That is actually one of the back-of-the-box selling point for most of these games.

But as one of those "games as art" kind of snobs, I also really like to have an engaging narrative that flows seamlessly with the gameplay. So if a game offers a narrative of any kind, you bet I'm going to judge the game based (at least in part) by how well that narrative works and how fully it is integrated into the core gameplay experience. And when a game tries to convince the player that they are destined to save the world from impending doom (as is often the case with big-budget, open world games), then I get really peeved when I find myself able to completely eschew that destiny in favor of picking flowers and peddling salvaged bandit armor for the next 100 hours.

A world in stasis

The source of most of the "limbo" comes down to the fact that these games' worlds (despite being big and detailed) often feel static and devoid of life. They don't change on their own. No one seems to have any sense of agency, and nothing ever happens unless the player is there to make it happen. Quest-givers sit around outside their house forever waiting for the player to come along and help them kill the wolves that are attacking their livestock, or find their missing heirloom, or deliver their special package to someone in the next town over, or whatever else they want done. The situation never resolves itself, the quest-giver never gets tired of waiting for you and hires another adventurer, those wolves never manage to eat all the remaining livestock, the heirloom never shows up in lost-and-found, and the statute of limitations on that package never expires. Emergencies can always wait [indefinitely] for the player to resolve them.

Quest-givers will wait forever for the player character to show up and solve their problems.

But worst of all is that the big, bad villain (if there is one) just doesn't feel very threatening or intimidating if he (or she, or it) isn't actually doing anything to actively antagonize the player or the world. They just sit in their castle or on their mountain or in their dungeon or whatever and wait. They're in no rush to set off their evil plans and complete whatever objective they have. They rarely (if ever) swoop down and make any actual effort to stop the hero or whatever authorities exist in the world that might stop them. The villain sits and waits for the player character to come and stop them. Because of this, it's hard for a sandbox game to have an interesting or compelling villain if that villain never seems to influence the game world or character in any negative way.

No sense of urgency

The purpose of holding these quests in stasis seems to be to allow players to play as many quests as they want in a single playthrough. After all, the player wants to be able to see as much of the game as possible right? And the developers want the players to see all of the content that they dedicated so much time, sweat, and tears into crafting. Players of open world games want to have organically developing quests, so that you can set off in some direction and find new quests to take on as you travel, rather than having to beeline somewhere to complete a quest before an arbitrary timer fails you. And these are all perfectly valid design considerations!

But once you know that quests will wait indefinitely for you to resolve them, it takes away any sense of urgency that you might have had to resolve them. There's rarely (if ever) any reason in a video game RPG to ever turn down a quest, even though the player will usually have the option to respond to a quest giver with something along the lines of "I don't have time for that right now". And this is an option that players should be willing to use, since there should be some quests that are just more important than others. But even if you do have more pressing matters that you want to attend to (because you never actually need to attend to them), you can still just accept the quest anyway. It'll go into your quest log, where it will sit for the rest of the game unless you decide to pick it later. Even in a game like Fallout that has a karma system, you're never punished for agreeing to take on a quest that you never actually attempt.

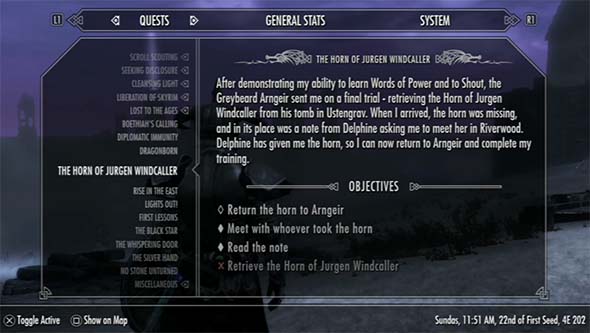

The big and complex worlds of The Elder Scrolls can feel stale once you realize

that crises are more than happy to wait around until you come to single-handedly resolve them.

Even emergencies can often wait until the player's convenience. The best example is the Oblivion gates of The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion. They are supposed to appear in towns and daedra start streaming out of them, forcing the player to have to quickly intervene to save the town and its inhabitants. But in reality, it doesn't matter when you get to town. The Oblivion gate will be there, and the town will be in no better or worse condition than if you had shown up at any other time.

The main quest in the early half of The Witcher 3 had the same problem. I'm supposed to be desperately searching for Ciri, but I'm perfectly free to forget about her completely and go off on random contracts and treasure hunts, or just explore the world for weeks or months of in-game time. Ciri will be just fine when I get around to finding her. What's worse is that after you find her, the game gives you an open objective to go do all those quests that you may or may not have been doing already. So now I feel like neither rescuing Ciri nor fulfilling anyone else's quests was ever particularly important.

What games like this should do, is offer a quest that the player can fail due to inaction, or by choosing another objective instead. This would set a precedent that later quests or objectives are also timed, that "priority quests" should be treated as a priority, and that your failure to resolve the quest will have consequences. The potential for failure (and for game consequences) must be made readily parent to the player as early as possible so that the player doesn't feel like the rules are suddenly, and unexpectedly, being changed (I'm looking at you, Mass Effect 2!). And this leads to the second point...

Little or no consequences for action (or inaction)

Sephiroth will wait around for you to level enough to beat Ruby Weapon. No rush.

So we've seen that there's rarely any reason to ever commit to a single quest (or set of quests). But once you've committed to a quest, this lack of urgency exposes a corollary problem: there aren't any consequences for your action or inaction resolving the quest. In order for all the quests to still be open and accessible, the game has to avoid making sweeping changes to the world or any of its areas. There might be a few mutually-exclusive quests in which completing one effectively cancels the other (or renders it un-obtainable), but these only happen in very select circumstances, and they're almost always presented as an obvious dichotomy (e.g. "Join the empire or join the rebels", "help one character instead of another", "do the 'evil' thing or do the 'good' thing", etc).

Your failure to clear out that dangerous bandit camp in a timely manner isn't going to result in the bandits ransacking and destroying the vulnerable town. Thus, there's no urgency to challenge the bandits, and absolutely no punishment for neglecting it entirely, and that quest (and its experience and other rewards) will still be available for you to complete whenever you feel like getting around to it. The wolves attacking a farmer's sheep will never eat all the sheep. That town in Oblivion is going to be just as destroyed whether you show up to save it right away or spend an in-game year picking flowers in the countryside. Getting there sooner doesn't save more people. Getting there late doesn't result in the town being nothing but a blood-and-debris-filled crater. Blackbeard in Assassin's Creed: Black Flag will delay his raid on Florida without complaint while I circle the Caribean twenty times plundering ships and hunting for random treasure chests. Ciri in Witcher 3 is going to be just as alive whether it takes you two weeks to find her or two months. Delaying doesn't affect her condition in any way. And grinding all the way to level 99, breeding a water-walking chocobo to find Knights of the Round, finding the underwater breathing materia to beat the Emerald Weapon, gambling in the Golden Saucer to win the materia combo that lets you clone Knights of the Round 16 times at the start of battle, and then using it to kill the Ultima weapon outside the Golden Saucer, still doesn't result in Sephiroth having already finished the Meteor summon by the time you begrudgingly wander into the Northern Crater because you've run out of other things to do in the whole world. Not that it would matter, the planet ends up saving itself anyway, making your whole quest moot, but oops, SPOILER ALERT!

The villains who want to destroy Megaton aren't a genuine threat because only you can detonate it.

Pretty much the only time that any major changes ever happen in such games is when they are the result of an affirmative action by the player. Probably the most popular modern example of this is destroying megaton in Fallout 3, which can only happen if you do it yourself. The villains who give you the quest will never just do it themselves, and so there's no real pressure to stop them and no consequence for failing to foil their plot. Similarly, completing the quest to join the Stormcloaks or Empire is the only way to ever get the Skyrim civil war kick started. Completing some quest may occasionally earn you the wrath of another NPC that might result in some pseudo-random encounter in which bounty hunters come after you. But gain, this is the result of an affirmative choice by the player. The random townie who asked you to deliver a package to her friend on the other side of the continent is never going to hire mercenaries to go find you if you fail to complete the delivery - even though that basically constitutes theft. So there's never any reason to turn down a quest that you can't (or won't) do because there's never any punishment for not completing the quest.

Option paralysis

Another subtle - but much more noticeable - effect of an open world sandbox can be "option paralysis". This is a state in which the player might have more open quests than you know what to do with, and you can't decide which quest to pursue next. Since none of these quests have any sort of priority or expiration, there is no mechanical reason why you should have to pursue one instead of another. Maybe your choices are based on which quests are closest on the map, which ones have the best perceivable reward (i.e. loot), which ones are lowest level, or maybe you have some specific role-play reason why your character wants to chose one over another.

A quest log overloaded with filler and no real reason to do any of them.

But if you've ever spent several minutes staring at your quest log or overworld map wondering "where should I go next?", that is a direct result of the game's sandbox design! This, in fact, is where the "limbo" comes in. It's that indecisive time in between quests when you just don't know what to do. Maybe you chose to take care of lose ends and travel back and forth notifying quest-givers that the quests have been completed, dropping off items, and collecting rewards - more tedious busy-work rather than any actual game play. But even once all that overhead is done, you still find yourself right back in the same position: there's no one quest that needs immediate attention, and so you don't know where to go next.

And it certainly doesn't help that much of the content in a sandbox game can feel copy-pasted. How many of those damn barrow crypts did you wade through in Skyrim? How many enemy strongholds in Assassin's Creed? It's hard to feel motivated to do anything if you feel like you've already done it a dozen times.

This is different than a situation in which you can't decide between one or more quests that you want to do, or that you need to do. That is actually a meaningful decision that games should have. The problem is when you don't necessarily want to do any of the quests, and there's no need to chose any one over another.

Other genres and paradigms have resolutions to these problems

Option paralysis is a common problem in other game genres and paradigms as well. Strategy games, simulation games, and (to some extent) horror games can also create situations in which the player either doesn't know (or can't decide) where to go (or what to do) next.

Survival Horror and adventure games can leave the player confused where to go or what to do next.

But there is a key distinction between not knowing what to do, and not being able to decide what to do next. A classic point-and-click adventure game or survival horror game might have a puzzle that the player can't figure out. This may result in wandering the environment in circles trying to find an item or note that provides a solution or clue, and it can be frustrating, and could very well be indicative of design flaw. But this is a completely different situation than an open-world RPG having thirty open quests in my log - any of which I could go do (and know how to do) - but the game doesn't give me any compelling reason to go do any of them. Even when lost or stuck in an adventure or puzzle game, I'm still actively searching for a solution.

A strategy or simulation game can easily fall victim to "punctuated equilibrium": a problem in which the player has resolved most or all the conflict in the game and doesn't want to take any affirmative action that risks disrupting that peaceful state. A good example of this is when you balance your workers and your job availability in a city-builder and then don't want to zone any new houses or businesses. You have lots of options for buildings, but don't want to build any because you risk toppling the economic scale that you've so delicately balanced.

Another good example is in strategy games like Civilization or Total War. Players of these games can easily fall into a pattern of just queuing up new things to build and hitting "end turn". Perhaps you need to expand, but you can't decide which rival nation to declare war on because you're in a peaceful state with all of them and are openly trading. So you sit on your haunches and play the game passively.

These games, however, resolve the option paralysis problem by having systems in place to upset the status quo and force the player into taking actions - or at least, good ones have such systems. A good city builder (like Cities: Skylines) might have citizens that age over time and drop out of the work force, forcing you to invite younger citizens to replace them; land values might fall and decrease tax revenue, making a business unprofitable or forcing you to raise taxes; or resources can be depleted in order to force you to expand your city or industry to acquire more. Having a game environment that is non-static inherently creates organic problems that the player eventually needs to resolve.

Resource-depletion in a strategy or simulation game might force the player to take action.

Strategy games like Civ, Total War, Europa Universalis, and so on can break the player out of a monotonous, indecisive limbo through the active agency of the player's A.I. competitors. Other empires don't necessarily just sit around waiting for you to interact with them. They will come to you with offers of trade deals, diplomatic treaties, or declarations of war. These actions by the A.I., and your choices on how to resolve them will have ripple consequences with other agents in the game world. Even a passive action like initiating a trade deal with one empire might upset their rival, creating conflict.

Open world games designers who want to make a game world that feels alive should look at these other genres for inspirations. Having active agents in the game with their own agendas, or entropic systems that gradually erode the status quo, can make a game world feel much more engaging and alive. It can also make the characters much more personable or memorable. Any player of Civ will likely tell you that he or she has some list of hated A.I. leaders - whether it be Alexander the Great's expansionism, Shaka of the Zulu's violence, Montezuma of the Aztec's forward-settling, Napoleon of France building all your favorite wonders, or Dido of Carthage's deceitfulness, or any other A.I. that consistently foils your plans. Heck, some people even hate Kamehameha of Polynesia for being "too nice", but always settling that annoying city on your unclaimed coast.

A.I. players in strategy games can force a player out of option paralysis.

Sure, it might alienate some players who like just having a big, free sandbox to play in, but you could always just include an option to turn such features off if you really want to cater to those kinds of players. The Sims (after 2) has characters that age and eventually die, so that you have a limited time to complete that character's goals. But you also have the option to turn aging off in the menu, so that you can spend more time playing that character, if you so desire. Fallout: New Vegas included an optional "hardcore" mode that required the player to stop to sleep, eat, and drink occasionally, or else suffer negative consequences that eventually lead to death. These sorts of mechanics are a start.

Breaking character

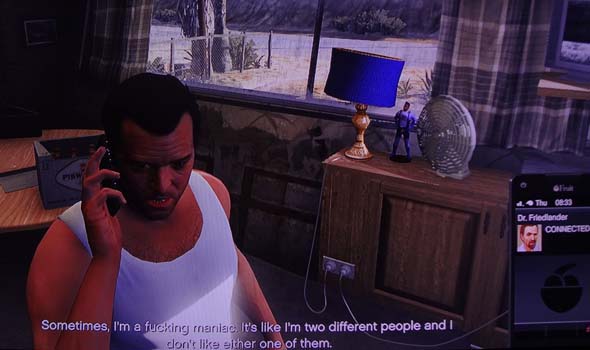

In addition to interfering with narrative development, an open world design can also interfere with character development. This is particularly problematic in games with defined characters, since playing them "incorrectly" also conflicts with their established, characterizations written by the game's writers. Games like Skyrim, Mass Effect, and Fallout avoid these problems by having completely customizeable characters that act as personality-less avatars for the player. The player character has no established personality or ethics, and so the player is more free to make whatever choices he or she wants without breaking character. Games that rely on established player characters (such as Final Fantasy, The Witcher, and Grand Theft Auto (after GTAIII)) can run into big narrative problems when the actions and dialogue of the character in cutscenes completely conflict with the player's behavior in-game.

One of my favorite example of this problem is Grand Theft Auto IV. It can be hard to take Nikko Bellic seriously as he bemoans war, crime, and violence in countless cutscenes, if you just shot your way through a gunfight with police after lobbing grenades at cars stopped at red lights simply because you can. It makes the character seem inconsistent at best, and outright insane and completely unrelatable at worst. It's almost impossible to let yourself be pulled into a game's story if the gameplay actively conflicts with the story.

Nikko Bellic bemoaning his past deeds as a soldier for hire rings hollow if the player

willingly engages in the meaningless chaos that Grand Theft Auto IV's sandbox enables.

GTA IV is really two different games. If you show some restraint in your free play gaming and focus on progressing missions, character interactions, and the narrative, then the story that was written becomes an expertly-crafted masterpiece with lovable characters, a heartbreaking ending, and a stark warning of the consequences of a life of crime. This fatalist message becomes an answer to the critics, pundits, and politicians who accused the game of glorifying violence to the youths who played it. But if you avail yourself of the sandbox chaos that the game and its various side content enables, then all those emotional connections with characters, strong narrative themes, and powerful anti-violence messages completely disintegrate, and the story only serves to get in the way of the fun sandbox chaos.

This is why I was intrigued by Grand Theft Auto V's multi-character design. I had assumed that each character would have a distinct personality and that the gameplay mechanics available to them would reflect that personality and help craft a tighter narrative with stronger characterization and consistent themes. I thought one character would be a white-collar criminal who appears to be straight-edge and never gets his hands dirty (Michael). Another would be a complete psychopath with no reservations about mowing down people because they had the misfortune of being in his way (Trevor). And the third, I guessed, would be somewhere in between: a ganbanger who wants out, or an ambitious protege trying to get in (Franklin).

All three characters in GTA V are actually deliberately intended to be as schizophrenic as

GTA IV's disconnected narrative and sandbox gameplay unintentionally made Nikko seem.

To some extent, that is exactly how each of those characters appears at first, but the designers still couldn't keep these characters internally consistent or provide enough variety of gameplay mechanics to suit their supposedly distinct personalities. Trevor definitely fits the role of the psychopath character that was planned for him, but the other two weren't any less chaotic. The end result was that I felt like I was just playing three copies of the same character in different clothing. I never got any sense of the different characters' personalities coming through in gameplay. Sure, each character has one or two unique side quests available to him that emphasizes his socio-economic condition. Trevor has his rampages and drug-smuggling, Franklin has his street races and tow-truck driving, and Michael has ... golf? But the core gameplay and possibility space doesn't change between characters. Regardless of which character I had selected, I could steal the same cars, buy and shoot the same guns, do the same stock trades, visit the same strip clubs, and sleep with the same strippers. It wasn't the case that one of the characters simply didn't know how to use a gun (or outright refused), thus changing the possibility space available to the player when using that character.

In one of the latest examples, The Witcher 3, Geralt is supposed to be searching for his proxy-daughter, Ciri. She's being pursued by an entity called the Wild Hunt, that seems to basically be the Ring Wraiths from Lord of the Rings. They are one of the most dangerous entities in the world. Geralt's dialogue makes frequent references to how important it is to find Ciri quickly, and how much danger she is in. Despite Ciri's imminent danger, the player is perfectly free to spend all the time they want exploring every nook and cranny of White Orchard, Velen, Novigrad, and Skellige, doing dozens or hundreds of side quests, without putting any efforts towards learning anything about Ciri's location or status.

This makes Geralt feel disingenuous in his affection for Ciri when he remarks on the importance of his main quest, and it serves to separate the narrative from the gameplay. It also effectively sucks all tension and suspense out of the plot, and weakens the Wild Hunt as a threatening villain. No matter how far behind Geralt seems to fall, the Wild Hunt is always just as behind, and seems just as incapable of finding Ciri.

Fallout 4 suffers from almost the exact same problem.

Open world isn't alone in this guilt

Admittedly, completely linear action games can also very easily fall victim to this problem. Any game that wants to tell a deep, complex story with developed character arcs is at an extreme risk. I criticized games like The Last of Us and Tomb Raider (2013) for this same sort of narrative / gameplay disconnect.

Those games (among others) loaded the actual playable parts of the game with action scenes and set pieces that were completely separated from the story that the cutscenes were trying to tell. The Last of Us wanted to be about the growing bond between Ellie and Joel, whether individuals' rights trump the good of civilization, and what people are willing to sacrifice to protect their loved ones. The cutscenes and dialogue all present those themes exceptionally well, but the gameplay completely ignores them. The interaction between Joel and Ellie (and Ellie and the game world) are limited during actual gameplay, and aside from a few small puzzle-platform bits, Joel and Ellie rarely have to interact and solve problems together.

Further, the player never has to make meaningful decisions that influence your ability to survive. You scavenge for supplies, but each supply is counted separately, so you never have to chose between, say, medicine or bullets. and only a couple crafted tools are really useful. Finally, the game never gives the player any meaningful decisions when it comes to the treatment or interaction with other characters. The entirety of gameplay is about sneaking around and killing people. You're only interaction with other characters in gameplay is to murder them. You never come across a group of fellow survivors and have to decide whether to approach them peacefully, rob them blind, kill them for their supplies, or avoid them entirely; and that sort of decision never has any bearing on the relationship between Joel and Ellie. And no matter how stealthy or murderous you play the game, you're railroaded into watching the same cutscenes depicting the same development between the characters.

Similarly, Tomb Raider wanted to craft a story about how Lara Croft becomes a survivor and explorer, but the whole game is a linear, on-rails shoot-em-up. Sure, there are optional tombs to explore, but they are pitifully short and simple, and the game never makes that a priority. Lara's character arc is also completely resolved within the first hour of gameplay, but the game drags on for another six or eight hours. The naive girl struggling to survive in an untamed wilderness during cutscenes is completely replaced with a merciless killing machine once gameplay begins. She grows more confident in herself as the game progresses, but the player never felt like a vulnerable victim to begin with. The bow and arrow tutorial early in the game requires you to shoot and kill a deer in order to feed yourself, but there are no survival mechanics at all after that.

But even though linear action games can easily fall prey to the same issue, open world games are at a much greater risk of severe character dissonance. The scope of the world, and the amount and variety of content that often has to be included in such games can rarely be as tightly choreographed and controlled as mini-games or side content in a much more linear game.

Examples (new and old) of getting it right

It's worth noting that open worlds are not a new concept, and there are actually quite a few very good examples of games (old and new) that managed to avoid or mitigate the problems that I outline above. I'm going to highlight a few notable examples of open worlds of gaming past, as well as one of the finer, more innovative examples in recent memory. If you have other ideas of particularly believable open worlds, or of creative ways that developers have avoided limbo, I invite you to leave a comment below.

Fallout remains a gold standard for western RPGs

My usual gold standard for an open world game that does an excellent job of forcing the player to progress is Fallout. The player is tasked with finding a replacement water chip for your vault's (i.e. underground apocalypse bunker) water recycler before the vault runs out of water. You have 150 in-game days to find a replacement chip or else everyone in the vault dies (that is, all the friends and family that your character has ever known), and you get a game over that boots you back to the title screen. Don't worry, it's plenty of time, and you can also complete other quests to extend the time by finding other ways to supply the vault with water. But having this ticking clock on your menu really puts pressure on the player to not waste time, especially if you have no idea how forgiving this time limit is.

Failing to find the water chip within the allotted time results in a "Game Over" in Fallout.

Arbitrary time limits are actually one of my biggest pet peeves in video games. Putting some ridiculously strict time limit on a level or objective in order to add challenge is one of the biggest design crutches in the history of the industry. To me, it shows that the designers aren't competent enough to make a genuinely challenging game, so they just fail you if you can't do it as fast as they want you to. The annoying time limits of old games like Driver really frustrated me. If I'm two seconds short of hitting the finish line before the timer runs out, but I've completely lost the police, it's just game over for no good reason. This was especially true because Driver was an open world game in which you had virtually unlimited options of paths to your destination, but the increasingly-strict time limit forced you to learn (through trial-and-error) what the optimal path was. Your skill as a driver, and your knowledge of the map wasn't being tested; only your ability to find the optimal path.

But if a time limit provides a reasonable margin of error and also has a justifiable reason for its existence, them I'm tolerant. Having to take out the terrorists in a Tom Clancy game before they kill a hostage provides a reasonable time constraint. Having to drive your ambulance via the optimal path to a hospital before a patient bleeds out is a reasonable time constraint. Having to disarm a bomb before it explodes is an acceptable use of a time limit (unless you have to swim through electric seaweed to get to the bombs!). These are all situational though, and a game can wear thin if such conditions are arbitrarily imposed on every mission or objective.

Fallout's time limit makes sense. People in the vault will die if you don't get water to them. That's a perfectly understandable consequence. The time limit is also reasonable and forgiving. The 150 days is several times more than you need to actually complete the quest, so you have plenty of time to do some side quests and get lost in the desert for a while. But you can't faff about indefinitely. At some point, you have to hunker down and get the job done. Having to decide which quests to pursue, and which quests to abandon also really puts the player in the shoes of the character, which is exactly what a role playing game is supposed to do!

You have to make hard decisions. And these decisions have consequences. People and whole settlements will be positively or negatively impacted by you completing quests for them or ignoring them (or never even encountering them). Reaching certain points in the story or completing certain quests will have ripple effects on other people and places on the map, and all in reasonable ways. It interacted well with karma system of that game, and it really helped to make the wastelands feel like a living place (ironically) populated with people that have needs and agendas, rather than just being a collection of things to check off a list.

Majora's Mask substitutes static limbo for time loop limbo

And then there's The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask. Full disclosure: I've never actually played this game, but I've heard and read a lot about it and discussed it at length with my Zelda fan friends. But anyway, Majora's Mask also puts a strict time limit on the player: you have three days to stop the villain from destroying the world. What sets this game apart is that the villain actually succeeds - multiple times - and the player must engage in Groundhog Day time travel loops in order to stop it.

In Majora's Mask, the world goes on (and ends) with or without you.

The whole world during these three days goes on about its business, oblivious to its pending doom. At the end of those three days, the villain (not Ganandorf, who could learn a thing or two from this other villain) pulls the trigger on his doomsday weapon and destroys the world, forcing Link to go back in time again to use his ever-growing knowledge of the game world to stop it. So while the consequences for failure aren't as dire as a Game Over, there is a constant sense of pressure to do only the things that are useful to your end goals. And the world itself, is certainly not suspended in static limbo, even if it is in a time loop limbo.

I cite this game as an example for two reasons:

- It is an example of a game with a living world, as NPCs have set schedules that they follow independent of the player character.

- It demonstrates that a game doesn't need a strict FAIL condition to have consequences.

The Reapers of Mass Effect 2 are actual antagonists

Imposing time limits isn't the only way to force the player to progress or provide a sense of a dynamic world. Mass Effect 2 is an example of a game in which the player must drop everything to address emergencies. At several points in the game, the Reapers will attack, and the player must immediately drop everything to intervene. This creates a building sense of dread, and makes the Reapers feel much more like active agents in the game universe. They have some agency of their own and act as actual antagonists. They don't sit around waiting for you to come and kill them; they are doing their thing. Granted, these attacks are scripted to occur after you complete certain quests and or milestones, but the fact they interrupt whatever you currently happen to be planning, and must be resolved immediately, creates a sense of crisis and urgency and discourages unproductive side questing.

When the Elusive Man contacts you about an emergency, you don't have the luxury of putting it at the bottom of your quest log and continuing on with whatever task you were already pursuing. You have to go now! All the other quests will still be there waiting for you when you're done with the Reapers. But these attacks serve to give the player a kick in your complacency and a little push back in the direction of progressing the narrative, as well as helping to maintain the drama that the narrative is building. It makes the Reapers feel threatening and frightening.

Mass Effect 2's Reapers are a villain that actually antagonizes the player with their own sense of agency.

In addition, almost every side quest is something that is directly related to your attempts to confront the Reapers. Most of your side quests involve recruiting team members to help you against the Reapers, and then securing the trust and loyalty of those team members. Other quests involve gathering resources and developing new weapons and technologies for the sole purpose of confronting the Reapers. It all contributes to a sense of progression towards a single goal and doesn't feel completely superfluous. It's a game in which the player never loses track of what your end goal is, and what you're trying to accomplish.

Shadow of Mordor sets a new standard for organic story-telling in a sandbox setting

One of the most intriguing games to come out in recent years is Monolith's Shadow of Mordor. I cannot say enough good things about this game, and it's easily one of my favorite games in recent memory. This game includes a completely open sandbox world. It's scripted narrative is fairly short and the world itself is fairly confined and limited in scale. But these constraints of design work in the game's advantage because it creates a nice, tight package in which the whole game revolves around its central premise: the power struggles between orc captains.

Instead of creating a world in which a story takes place, the world of Shadow of Mordor (in many ways) is the story. It is in a state of constant flux, telling a dynamic, unscripted story that the player engages in and contributes to. Much of how this story unfolds is directly contingent on player actions (changes in the orc hierarchy only happen when the player dies), but there are also many elements of this system that are outside of the player's direct control. Orcs that you have never interacted with will challenge other captains (that you may or may not have ever encountered), and the "Sauron's Army" menu can become littered with unknown, shadowy uruks operating with their own agendas, completely independent of anything that the player has done.

The uruks of Sauron's Army engage in their own agendas independent of player actions.

Imagine if a system like this had been included in Skyrim, and the various jarls were constantly fighting with each other for power over the handful of holds (Game of Thrones style). They'd raise armies, hire body guards, plot to assassinate each other, and form alliances, all happening in the background whether the player is aware of it or not. You could walk into Whiterun one day to find Jarl Balgruuf sitting on the throne. Then come back a month later to find that Ulfric's army has sieged and captured Whiterun, and Balgruuf has been replaced with Vignar Gray-Mane as jarl. If you find out what Ulfric is planning, but wanted Balrgruuf to remain in power, you'd be under some pressure to get to Whiterun before Ulfric's army in order to warn him or fight along his side. And you'd have to decide whether that was important enough to pull you away from whatever quest you were currently working on. Could that work and be fun? Maybe. I think so. Instead, Skyrim allows you to wander off for weeks or months of in-game time doing whatever random quests suit your whims.

One of the clever qualities of Mordor is that the uruks don't perform their own missions unless the player dies. So even though their specific actions are out of your control, how well you play still has an impact on this organic story. It's an excellent compromise that maintains the sense of individual agency for the uruk captains, without the game degrading into a confusing mess of constant re-alignments and seemingly random character shuffles. It's not based on a cycle of Musical-Orc-Chairs set to an arbitrary timer, nor is it based on an asinine Rube-Goldberg machine of nested if-then conditions that the player would need a spreadsheet to make any sense of. The system is simple, and as long as you continue to play well, your plans won't be foiled by a random number generator or an invisible stopwatch.