Since I have some extra time off for this holiday season, I'm trying to go through some of my backlog of shorter indie Steam games in between bouts of Cities: Skylines and Beyond Earth: Rising Tide. One such game is Facepalm Games' 2013's sci-fi indie hit, The Swapper, which I picked up in a Steam sale like a year ago. The game has also been ported to many consoles, including the PS3, PS4, Vita, XBox One, and Wii U, and the ports were developed by Curve Digital.

Making my clones do the deadly work

The Swapper seems to owe a lot to Valve's mega-hit Portal. Both games' central mechanics revolve around the player character using a futuristic non-weaponized gun (with 2 settings) to solve platforming puzzles and explore an environment. Portal is in full 3-D, whereas The Swapper is a more traditional 2-D side-scroller. The bigger difference however, is that the gun of The Swapper doesn't fire portable wormholes; instead, it allows the player character to instantly create clones of herself, and to swap her consciousness into one of the clones. Once created, these copies move in tandem with the copy that is currently being controlled by the player. The key to the puzzles is to maneuver yourself so that your clones can reach otherwise inaccessible areas or activate switches.

All your clones move in synchronization, making relative spacing very important for solving puzzles.

The space station is laid out in an unbelievable, but serviceable, series of puzzle rooms joined together by modest platforming sections. At first, the platforming between puzzles is interesting because it kept me thinking along the lines of solving puzzles rather than just moving from place to place. But there's a lot of exploration and backtracking, and having to navigate the corridors between puzzle rooms quickly became tedious once using the swapper gun became second nature and automatic. Fortunately, the game provides handy teleporters to allow you to quickly move to key sections of the station, so the backtracking never became as problematic as it could have been.

The puzzles themselves start off fairly simple, requiring that the player simply point the gun and clone herself in order to reach a platform or cross a gap and collect alien orbs that you use to unlock new areas of the space station. The challenge quickly escalates. Soon, obstacles start getting thrown at you, such as colored lights that prevent certain operations of the swapper gun, forcing you to have to find more elaborate ways around the lights in order to reach your destination. You have to start using careful positioning, choreographed movement, gravity, momentum, and inertia in order to successfully solve the puzzles. And all this escalation seems to happen naturally based on the increasing complexity of the levels, rather than through the introduction of new mechanics or controls.

About an hour into the game, I ran into a puzzle that took almost an hour of trial-and-error for me to solve.

About an hour into the game, the difficulty suddenly spiked, and I ran into one puzzle in particular that took me quite a while to figure out. I even had to leave it and come back to it later with a fresh perspective. I thought maybe I was missing some kind of upgrade or needed to learn some technique that the game hadn't tutorialized yet, but that wasn't the case. Eventually, I figured it out, and the solution seemed head-smacking obvious, but I probably spent a good hour on that one puzzle (approximately half of my time with the game, up to that point).

There are also some other sci-fi mechanics such as the occasional zero-g spacewalk, gravity inversion (allowing you to "fall" up and walk on the ceilings), and so on. These all flow fairly seamlessly into the game; although, I did feel that the gravity inversion felt a little unnecessary when it was introduced. After all, the game teaches you fairly early how to use the swapper gun to effectively fly by repeatedly swapping to clones created above you. This "flying", is, however, limited by the number of clones that you can create, and it's still subject to being blocked by colored lights. So gravity inversion felt superficial when introduced as a means of navigating the station. Once the gravity inversion was introduced into the puzzles, though, I recognized its value.

You'll also perform the occasional zero-G spacewalk or invert gravity.

Any problems that I had in solving a puzzle were purely intellectual. Every control and mechanic is intuitive and comfortable, movement is responsive, and I almost never struggled with making the character do what I wanted her to do. All in all, the game plays near-perfectly. The puzzles are appropriately challenging; although, the exploratory nature of the game means that difficulty can wobble back and forth a bit depending on which puzzle rooms you reach first.

Exploring the theme of identity through game mechanics

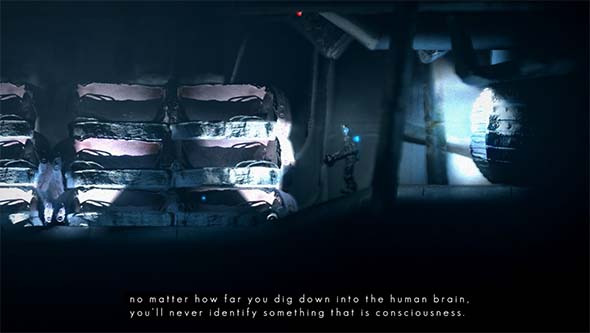

So the core mechanic and puzzles are simple, comfortable, and varied enough to make the game a joy to play. But where The Swapper really excels is in its narrative and themes. The written narrative is fairly simple and straightforward, with mostly predictable plot turns. But this narrative explores very complicated and metaphysical themes of consciousness, identity, and self, and those themes are actually conveyed through the game's actual mechanics!

This is what differentiates The Swapper from less compelling games like Lifeless Planet. Where Lifeless Planet is reliant on cutscenes, narration, and log entries to convey its themes and make its allegorical point, The Swapper doesn't even need dialogue, narration, or cutscenes in order to explore its predominant theme or make its point. It does have cutscenes, dialogue, narration, and text logs, but they are supplementary to the way that the game's mechanics themselves more than adequately explore the concepts.

It didn't take long for me to start to lose track of which clone was the "original" me, and the moment that I realized that the clones (including the "original") are all disposable, my head was spinning with the tough metaphysics of the scenario being laid out before me. Through the game's mechanics, The Swapper forces the player to ask yourself questions like "Who am I?", "Which me is me?", "Am I the same me that I was a minute ago?", "What is consciousness?", and so on. The game even goes so far as to ask "Do we have a soul?"

You'll soon be throwing copies of yourself into certain death in order to achieve your goals.

The written narrative, dialogue, and text logs, all further elaborate on this same theme by providing a debate on the metaphysics in question. The characters ask the same questions that the player is asking, and they also wonder at the ethical and moral implications of their discovery. Sadly, the gameplay never plays deeply into these more complicated ethical considerations (at least not till the very end), but the swapping mechanic should make it easier for a player to follow along with the questions that the characters ask and the implications that they bring up.

So when I complain about the stories of games like The Witcher 3 or The Last of Us being disconnected from their gameplay, this is the kind of thing that I'm talking about! Those games don't do what The Swapper does exceptionally well, which is to make its narrative and gameplay be about the same thing so that the two work together in harmony.

The story of The Last of Us can stand up on its cutscenes alone without needing to show more than a tiny fraction of the gameplay. But the story of The Swapper doesn't work without the actual game part because the act of playing the game is contributing to that story. When I ask "What is The Last of Us about?", you kind of have to give two answers: its about the growing bond between Joel and Ellie and the lengths we'll go to protect family; but the parts that you play are about surviving a zombie apocalypse by shooting things and collecting salvage. Two different things. When I ask "What is The Swapper about?", you can provide a single, concise answer: it is about the nature of consciousness and identity and the mind-body problem. One answer. Narrative and gameplay unity.

And the true brilliance is that the the simple act of playing the game goes so far to help explain the problem and make it tangible that I can't imagine anybody having trouble understanding the very heavy metaphysical concepts being discussed. It makes this complex philosophical conundrum accessible to its audience in ways that simply telling the story can't. It's a perfect application of the video game medium.

The story is just as mind teasing as the puzzles, and the two compliment each other brilliantly.

Even the visuals seem to add to the theme. Despite the visuals being composed of vivid colors starkly contrasted against dark backgrounds, there is an ominous grain effect overlaid on everything. This creates a sort of "fuzziness" in the aesthetic that may symbolizes the blurring of the sense of identity being experienced by the character. I'm not sure whether this was deliberate or not, but it worked well for me.

One of the best mechanical explorations of a concept

The Swapper is - put simply - one of the best examples of a video game that uses its mechanics to explore its concept and themes. Its story teases the mind just as thoroughly as the puzzles, and it was an immensely engaging and intriguing experience.